Perfume de Princesa

2013

Princess Perfume

Instalação

Museu da Cidade de São Paulo

(Beco do Pinto, Solar da Marquesa e Casa do Olhar)

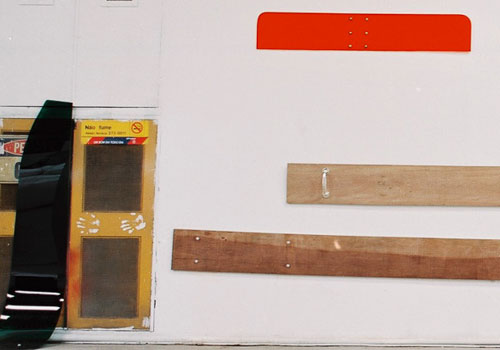

No centro de São Paulo a instalação serpenteia por todo o espaço unindo o Solar da Marquesa de Santos, a Casa do Olhar e o Beco do Pinto por meio da sua presença física e de diferentes aromas florais e corpóreos.

Instalation

São Paulo City Museum

(Beco do Pinto, Solar da Marquesa e Casa do Olhar)

In downtown São Paulo the installation meanders throughout the space gathering three historical spots, the Solar da Marquesa, the Casa do Olhar and the Pinto Alley with its physical presence and different scents.

Os odores dos outros

por José Bento Ferreira

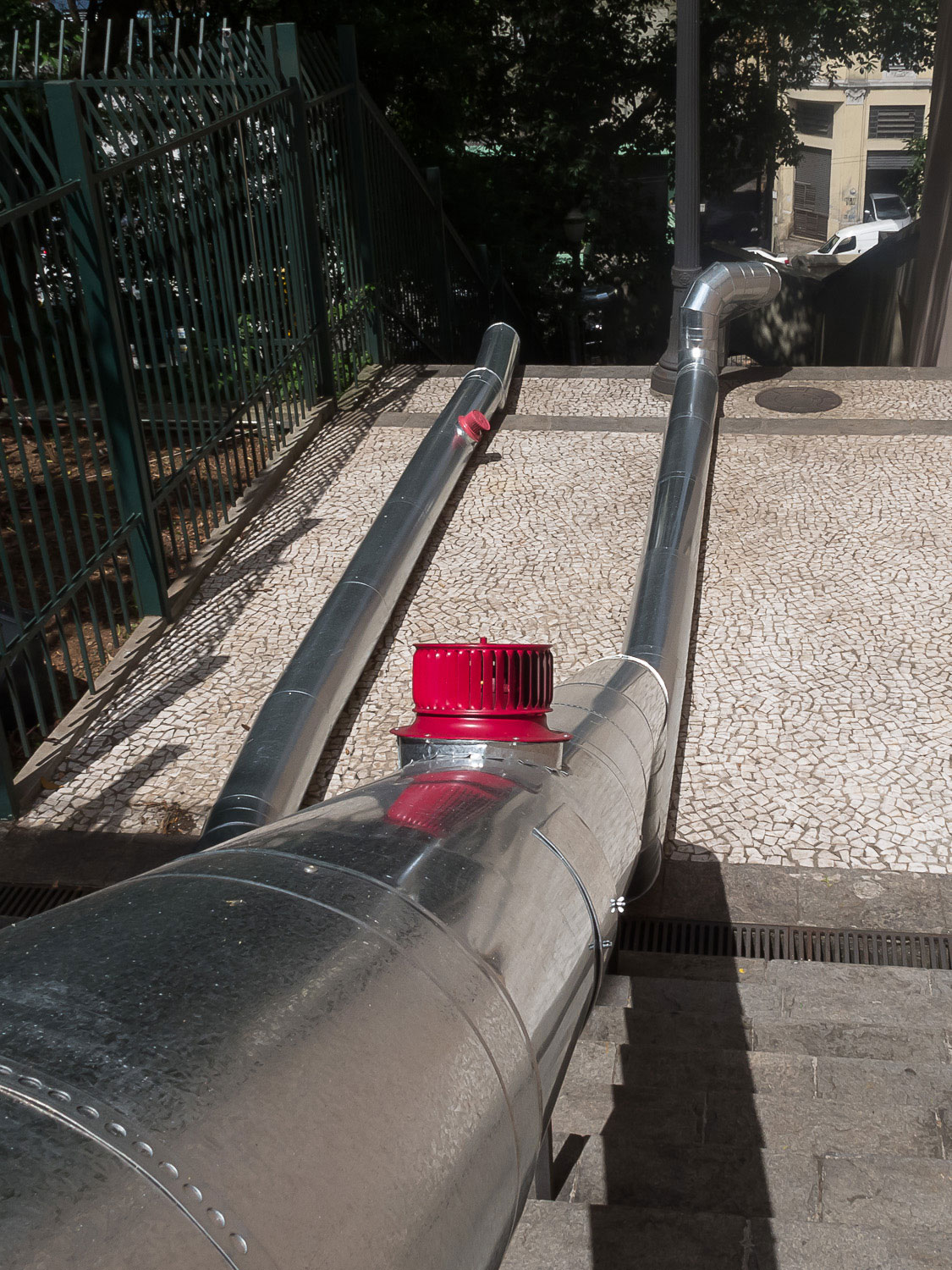

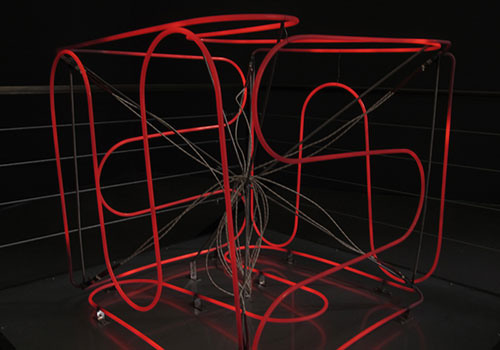

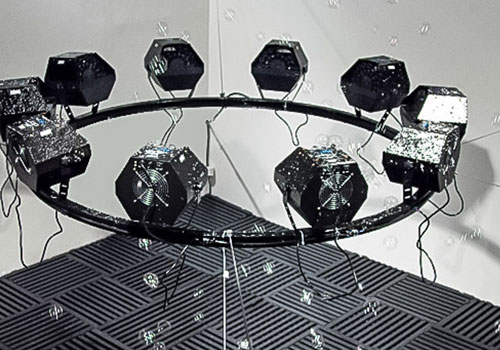

A primeira observação sobre Perfume de princesa é bem simples: a estrutura de tubos que serpenteia pela escadaria do Beco do Pinto faz parte do trabalho de Wagner Malta Tavares, tanto quanto os aromas exalados por ela em pontos específicos do caminho. Esculturas como Herói (2010) e Anúbis (2008), nas quais ventiladores são acoplados a tecidos e objetos semelhantes a sarcófagos, legitimam esta afirmação, que aponta para um tema caro ao artista: a integração entre arte e tecnologia. Apesar de Wagner Malta Tavares parecer otimista a respeito das possibilidades estéticas do uso de artefatos tecnológicos, a recorrência do tema e o modo como costuma ser tratado indicam que a questão não está resolvida para ele, precisa ser continuamente levantada e exige explicação.

Uma segunda observação também é simples: em contraste com sua perspectiva futurista, o artista olha para o passado ao pesquisar a história do perfume e considerar a memória do lugar. Apesar disso, Perfume de princesa retoma o vento como forma, o que já havia sido feito nos trabalhos expostos em 2010 pelo Instituto Tomie Ohtake, como observou o crítico Rodrigo Naves. Em lugar dos tecidos esvoaçantes e do vento batendo no rosto dos espectadores, a máquina projetada por Wagner Malta Tavares sopra essências florais ao longo da histórica viela da região central de São Paulo, pontuando o caminho dos passantes com matrizes tradicionais de perfumes como rosa, alfazema e angélica, entre outros. O Beco do Pinto transforma-se em túnel do tempo ao reconstituir a atmosfera olfativa do século XIX, presidida por Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo (1797-1867), que viveu um longo romance com Dom Pedro. A partir de 1834, ela residiu no casarão que passou a ser chamado de Solar da Marquesa de Santos e hoje pertence ao Museu da Cidade.

Uma reflexão um pouco mais ambiciosa pode ser feita a partir das observações acerca dessa experiência olfativa, que, por meio daquela estrutura tecnológica, lança um olhar dividido entre o passado e o futuro. A busca pela cidade ideal e a idealização da paisagem natural (como nos jardins ingleses) estariam ligadas, segundo o antropólogo Alain Corbin, a uma “acentuação da sensibilidade” a partir da segunda metade do século XVIII. O autor caracteriza certas medidas de saúde pública como uma “ofensiva contra a intensidade olfativa do espaço público”. O combate sistemático ao mau cheiro de esgotos, hospitais e prisões descrito por Corbin não se relaciona com uma liberação do uso de cremes, perfumes e outros cosméticos, mas com o seu disciplinamento

A história do perfume remonta ao Egito antigo (Gombrich comenta utensílios de perfumaria ornados com imagens dos deuses), mas entre os séculos XVIII e XIX substâncias aromáticas usadas tradicionalmente foram reprovadas por cidadãos aterrorizados pelo mundo microscópico revelado por Lavoisier e convencidos de que as virtudes cívicas provêm de um estado natural da humanidade. De acordo com uma ideia puritana de natureza, valorizam-se odores naturais do corpo, e o uso de perfumes recua. Até mesmo banhar-se passa a ser visto como um ato de vaidade potencialmente prejudicial à saúde. Colônias florais substituem os cremes produzidos a partir de substâncias extraídas de animais e passam a integrar um jogo de “códigos imperceptíveis” vinculado ao universo feminino, segundo a associação, que passa a ser contumaz, entre a mulher e a flor. Curiosamente, o revigoramento da nobreza intensificou o uso desses perfumes depurados como elementos de distinção social e dissimulação da sedução amorosa.

Biógrafo recente da Marquesa de Santos, Paulo Rezzutti cita descrições de viajantes admirados com a limpeza da cidade de São Paulo ao final do século XVIII. Poucas décadas depois, separada de Dom Pedro e vivendo no casarão da rua de Nossa Senhora do Carmo, Domitila exigiu a reconstrução do Beco do Pinto, invadido por um vizinho. Segundo Rezzutti, escravos encarregados de descer o Beco para atirar lixo no rio Tamanduateí por vezes o faziam no terreno da marquesa. Embora se aprecie o contato entre as pessoas de diversas gerações e classes sociais por meio dos seus aromas singulares, ou “impressões olfativas”, é impossível distingui-lo do controle social que cada indivíduo exerce sobre os odores dos outros e os seus próprios odores.

A fala de Wagner Malta Tavares que acompanha Perfume de princesa relata uma investigação acerca da Marquesa de Santos e problematiza a distinção entre a história factual e o imaginário. Concubina do imperador e benemérita paulistana, Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo potencializou a imagem da mulher paulista, que, ainda segundo Rezzutti, era tida por bela e independente. Sem pretender remover o fato da teia de significados que o envolve, no trabalho de Wagner Malta Tavares cristalizam-se fantasias, preconceitos, julgamento moral, idolatria: o túmulo de Domitila no Cemitério da Consolação tem sido venerado de diversas maneiras, e o perfume também é atributo dos cadáveres de santos

The odors of others

by José Bento Ferreira

The first observation about Perfume de princesa [Perfume of a Princess] is a very simple one: the structure of tubes that winds along the stairs at Beco do Pinto is as much a part of the work by Wagner Malta Tavares as are the fragrances it exhales at specific points along the path. This finding is substantiated by sculptures such as Herói (2010) and Anúbis (2008) – in which fans are coupled to fabrics and objects resembling sarcophagi – and it points to an enduring theme for this artist: the integration between art and technology. Despite Wagner Malta Tavares’s evident optimism about the possibilities of putting technological devices to aesthetic use, the recurrence of the theme and the way it is treated show that he has not yet resolved this question: it needs to be continuously raised and still demands an explanation.

A second observation is also simple: in contrast with his futurist perspective, the artist looks to the past when researching the history of perfume and considering the memory of the place. Nonetheless, Perfume de princesa recurs to the wind as a form, which was also done in the works shown in 2010 at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, as observed by critic Rodrigo Naves. Instead of fluttering fabrics and the wind buffeting the face of the spectators, the machine designed by Wagner Malta Tavares blows floral fragrances along the historical alley in São Paulo’s downtown district, punctuating the path of the passersby with traditional essences of perfumes, including rose, lavender and angelica. Beco do Pinto is transformed into a time tunnel with the reconstitution of the 19th-century olfactory atmosphere, headed up by Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo (1797–1867), who had a longstanding affair with Dom Pedro. From 1834 onward, she resided in the mansion that came to be called Solar da Marquesa de Santos, and which today belongs to the Museu da Cidade.

A more ambitious reflection could be made based on observations about this olfactory experience, which by means of that technological structure looks to both the past and the future. According to anthropologist Alain Corbin, the search for the ideal city and the idealization of the natural landscape (as in the English gardens) are linked to an “accentuation of the sensibility” from the second half of the 18th century onward. The author characterizes certain public health measures as an “offensive against the olfactory intensities of public space.” The systematic battle against the bad smell of the sewers, hospitals and prisons described by Corbin is not related with a freer use of creams, perfumes and other cosmetics, but rather with discipline in their employment.

The history of perfume goes back to ancient Egypt (Gombrich comments on perfume utensils decorated with images of the gods), but between the 18th and 19th centuries traditionally used aromatic substances were spurned by citizens terrorized by the microscopic world revealed by Lavoisier and convinced that the civic virtues stemmed from a natural state of humanity. In accordance with a Puritan idea of nature, the body’s natural odors were valorized, and the use of perfumes plummeted. Even taking a bath was seen as an act of vanity potentially harmful to one’s health. Floral colognes substituted creams based on animal extracts, and began to take part in a game of “imperceptible codes” linked to the feminine realm, in accordance with a strengthening association between the woman and the flower. Curiously, the reinvigoration of nobility intensified the use of these refined perfumes as elements of social distinction and for the dissemblance of amorous seduction.

A recent biographer of Marquesa de Santos, Paulo Rezzutti, cites descriptions by travelers who were struck by the city of São Paulo’s cleanliness in the late 18th century. A few decades later, separated from Dom Pedro and living in the mansion on Rua Nossa Senhora do Carmo, Domitila demanded the reconstruction of Beco do Pinto, invaded by a neighbor. According to Rezzutti, slaves tasked with going down the alley to throw trash into the Rio Tamanduateí would sometimes throw it in the marchioness’s yard. Although the contact between people of different generations and social classes by means of their singular aromas or “olfactory impressions” is appreciated, it is impossible to distinguish it from the social control that each individual exercises on the odors of others and their own.

By reconstituting possible formulas of perfumes from past eras and effusing them in places of memory (including inside the Solar and around a bathtub that the marchioness never used), Wagner Malta Tavares problematizes the distinction between factual and imaginary history. A mistress of the emperor and an illustrious lady from São Paulo, Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo Lindfors bolstered the image of the woman from São Paulo, who, also according to Rezzutti, was considered beautiful and independent. Without disregarding the web of meanings it is enmeshed in, Wagner Malta Tavares’s work crystallizes fantasies, prejudices, moral judgment, and idolatry: Domitila’s tomb at Consolação Cemetery has been venerated in different ways, and perfume is also an attribute of the cadavers of saints.

Perfume de Princesa

por Afonso Luz

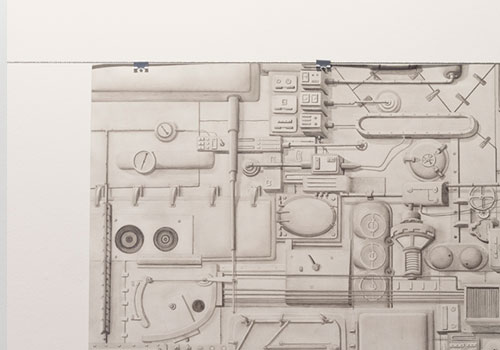

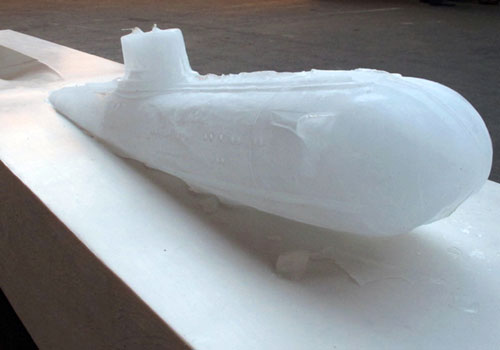

Atravessando planos, transpondo paredes, janelas e superfícies, a presença desta estranha tubulação (uma minhoca metálica que exala cheiros variadamente artificiais) nos dá motivo, atualmente, para pensar a costura de um espaço urbano fragmentário composto por três sítios históricos adjacentes. Sem dúvida, uma intervenção na escala proposta por Wagner Malta Tavares abre os olhos e as perspectivas desta vivência inusitada do centro histórico de São Paulo. Vemos ali um alinhavar imaginário de três documentos imóveis da cidade, suturando o sítio que se formou no período colonial e que perdura até a urbe contemporânea que nos habita.

Finalmente, e com grandes finalidades, pudemos enxergar neste processo de ocupação espacial um desejo do Museu da Cidade em transformar o Solar da Marquesa, o Beco do Pinto, e a Casa nº 1 em uma unidade comum de experiência. Aos poucos, o conjunto de bens urbano-arquitetônicos dispostos naquela colina histórica recebe marcas que transpõem interiores domesticados, potencializando suas características arqueológicas de sítios contínuos e frisando sentidos ao longo deste arruamento antigo que delimita também o quadrante da esquecida Rua do Carmo.

Uma curiosidade: o percurso que fazemos para ver a obra de Wagner é também, apenas por acaso, o de dois eixos

perpendiculares fundadores do território urbano. Um eixo replica a lateral do famoso triângulo que desenhara São Paulo em seu início de Vila desde o século XVI, talvez até ao século XIX. O outro, esse eixo também apagado que se plasmou como escadaria ligando a aresta do triângulo ao leito do rio Tamanduateí, forte testemunho da lógica colonial das passagens entre a “cidade alta” e a “cidade baixa”. Ambas as linhas são interrompidas pelo fluxo automobilístico que se impõe no século XX, como natureza dominante, redesenhando margens e marginalizando nossa memória.

Então, ironicamente, o sentido que percorremos pela obra acompanha o imaginário percurso da linha que formava, desde o Mosteiro de São Bento até o extinto Convento Carmelita, as geometrias constitutivas desta suposta triangulação de um território paulistano originário. Lembremos, ainda por ironia do destino, que reside também nesta rua o monumento solitário coberto de pinturas de Frei Jesuíno do Monte Carmelo, a quem Mário de Andrade dedicou um longo e célebre ensaio. São só vestígios de sucessivas épocas que hoje sobrevivem apenas na imponência de seu próprio tempo. Estamos longe de conseguir restituir qualquer horizonte em tantas camadas de tempo arruinadas, e as lembranças são apenas lampejos disformes dos acontecimentos que se apagam nos palimpsestos da cidade. É tão só a cidade que sonha consigo mesma.

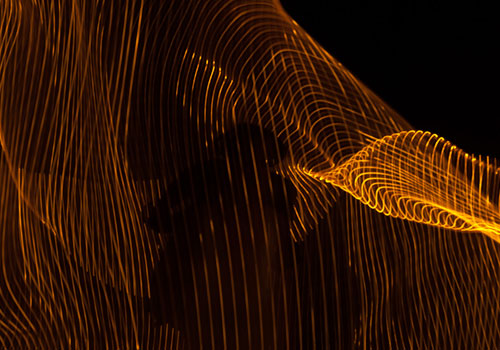

Wagner Malta Tavares desperta-a nestes atravessamentos. O que chamou Perfume de Princesa é quase uma escultura, bem ao feitio de “instalações” que fazem moda no presente.

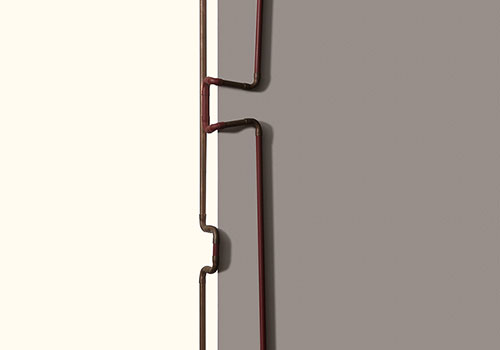

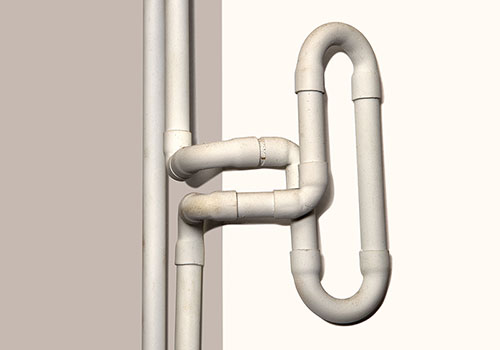

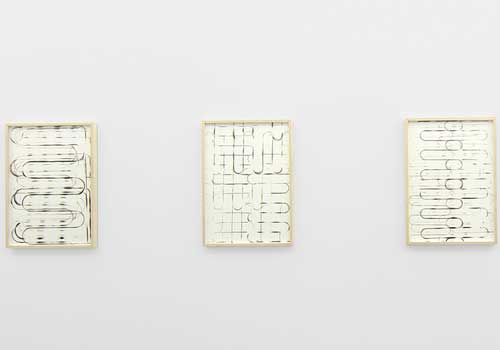

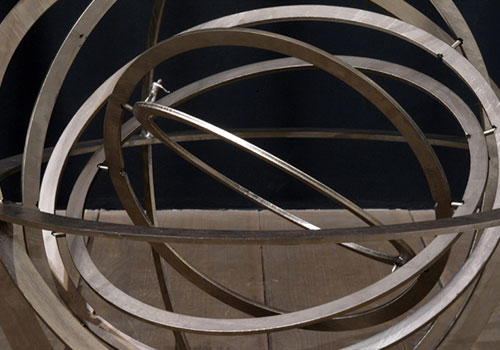

Interessa nela uma escala urbana modular, dispositivo que é capaz de estender-se por áreas imensas, uma modularidade que se avoluma e provoca dobras em cotovelos, o que poderia ainda conquistar inumeráveis direções. Esse complexo sistema vai enumerando contornos de espaços em adesões inusitadas à silhueta das superfícies edificadas, como se desconhecesse planos sensoriais que nosso corpo humano enquadra.

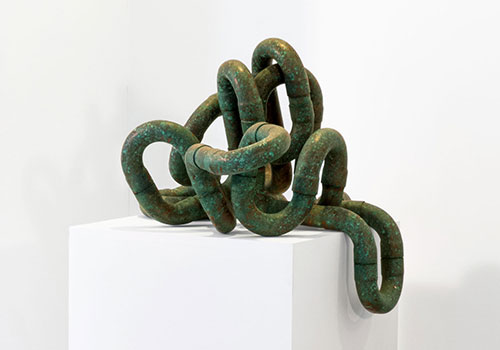

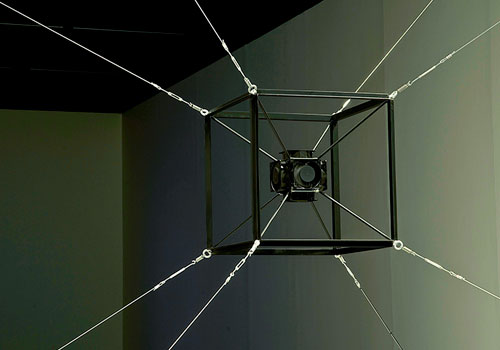

Há um momento de mais vigor estético no dispositivo imenso, agenciando ali a reversão do que parecia apenas um virtuosismo de ocupar o espaço (sempre maior quando o vemos no comprimento do beco ou nas vistas aéreas dos três edifícios em seus patamares). Essa experiência de intensidade se dá justamente quando entramos na sala aos fundos da Casa nº1 e, numa pequena área, os conectores galvanizados da tubulação passam a conectarem-se a si mesmos, em uma vertiginosa torção, levando com eles todo espaço interior, o que, por um instante, forma um abissal redemoinho espiralado, como se ali dessem tensão e velocidade ao extenso corpo vagaroso que conhecíamos de modo dissipado,

suspeitando, há pouco, de sua anedótica presença. Nesta pequena sala, emerge a “cobra grande” (ou é como se assim fosse). Ela, que descansava nos cantos das ruínas coloniais e nos cenários do patrimônio histórico, surgindo naquele cubículo com toda a sua imensurável força corporal e exercendo sua hipnose de monstro sobre o corpo do espectador. Este esqueleto de anéis metálicos, pelagem de réptil mecânico, move-se diante de nós, bailando seu singular serpenteado, a dar-nos um nó na visão. Ali, enovelada em si mesma, quase que abraçando seu coração com as voltas de seu próprio corpo, a vemos num instante mágico. E tudo fica ali, por isso mesmo, também no coração da cidade.

Princess Perfume

by Afonso Luz

Crossing through planes, passing through walls, windows and surfaces, the presence of this strange tubing (a metallic worm that exudes a variety of artificial fragrances) currently prompts us to think about the mending together of a fragmented urban space composed of three adjacent historical sites. Without a doubt, an intervention on the scale proposed by Wagner Malta Tavares opens our eyes and the perspectives of this unusual experience in São Paulo’s historical downtown. We see an imaginary patching together of three immobile documents of the city, suturing the site that was formed in the colonial period and still persists in the contemporary metropolis we inhabit.

Finally, and with great difficulties, we can perceive in this process of spatial occupation a desire of the Museu da Cidade to transform the Solar da Marquesa, the Beco do Pinto, and Casa nº 1 into a common unit of experience. Gradually, the set of urban-architectural heritage arranged on that historical hill receive marks that transpose domesticated interiors, potentializing the archaeological characteristics of continuous sites and asserting meanings along this arrangement of old constructions that also delimits the quadrant of the forgotten street called Rua do Carmo.

It is curious that the path we take to see Wagner’s work is also, coincidentally, that of the two perpendicular founding axes of the urban territory. One axis replicates the side of the famous triangle that gave the outline to São Paulo since its beginning as a small-town in the 16th century, perhaps up to the 19th century. The other is a likewise erased axis consisting of steps linking the corner of the triangle to the Tamanduateí River, a strong testimony of the colonial logic of passages between the “high city” and the “low city.” Both the lines are interrupted by the flow of automobiles imposed in the 20th century, as the dominant nature, redesigning margins and marginalizing our memory.

Therefore, ironically, the path we take as we move through the work accompanies the imaginary path of the line that ran from the São Bento Monastery to the no longer existing Carmelita Convent, the constitutive geometries of this supposed triangulation of the original territory of the city of São Paulo. We remember – also an irony of destiny – that this street is moreover the home of a lone monument covered by paintings by Frei Jesuíno do Monte Carmelo, to whom Mário de Andrade dedicated a long and celebrated essay. They are vestiges of successive eras that only survive today in the stateliness of their own time. We are far from being able to restore any horizon to so many ruined layers of time, and the memories are only misshapen sparks of the happenings that have faded away on the palimpsests of the city. It is a very lonely city that dreams about itself.

Wagner Malta Tavares awakes it in these crossings. What he named Perfume de Princesa is nearly a sculpture, in the currently fashionable form of the “installation.” It interestingly involves a modular urban scale, a device that is able to extend through immense areas, a modularity that grows with different folds and angles, with the ability to head out in countless directions. This complex system enumerates contours of spaces in unusual adhesions to the outlines of constructed surfaces, as though it had no notion of the sensorial planes framed by our human body.

There is a moment of greater aesthetic vigor in the immense device, where it operates the reversion of what seemed to be only a virtuosity of occupying the space (always larger when we see the length of the lane or in the aerial views of the three buildings on their different levels). This intense experience takes place precisely when we enter the room at the back of Casa nº 1 where, in a small area, the galvanized connectors of the tubing begin to connect to themselves, in a dizzying twist, bringing with them all of the interior space, which, for an instant, forms a spiraling abyssal whirlpool, as though they were lending tension and velocity to the extensive crawling body that we had seen in a dissipated way, a short time before suspecting its anecdotic presence. In this small room the “big snake” emerges (or at least it seems like that). It is the snake that was resting in the corners of the colonial ruins and in the scenes of the historical heritage, arising in that cubicle with all its immeasurable corporal power and exercising its monstrous hypnosis over the spectator’s body. This skeleton of metallic rings, the skin of a mechanical reptile, moves in front of us, winding its singular coil, tying a knot in our vision. There, wound about itself, as though embracing its own heart with the windings of its own body, we see it in a magical instant. And this is precisely why everything there is also in the heart of the city.

+ work

Medusa 4escultura2023

Orbital _azulescultura2023

K2-141bescultura2023

Orbital _amareloescultura2022

Medusa 3escultura2022

Relevo de Quina _vermelhoescultura2022

Passoescultura2022

Orbital _vermelhoescultura2022

Relevo de Canto _Cruzescultura2022

Voragemfotografia2022

Relevo de Quinta _brancoescultura2021

Figura Sentadaescultura2021

Medusaescultura2021

Relevo de Quina _azulescultura2022

Banhistasocupação2020

Íconesesculturas2020

Figurassérie de esculturas2020

Figuras IIsérie de esculturas2020

Medusaescultura2020

Sursum Cordaescultura2019

Vigilanteescultura2019

Lado Bexposição2019

Meteoroexposição2018

Jogos Perigososescultura + perfomance2017

Malpertuisescultura2016-2017

Sonda Dobrável - Fugaescultura + som2016

Vigilantefotografia2016

Sustenido #escultura2016

Theyinstalação2016

Horizonteescultura2016

Sonda Pretaescultura + som2016

Projeto para coluna de ventoescultura2016

Torre - Ground Controlfotografia2016

Sondaescultura + som2015

Monotipia Térmicamonotipia2015

No calor da horainstalação2015

BangCrunchinstalação2015

Diário do Capitãodesenho2015

Círiosinstalação2015

Equilibristaescultura2015

Pipoca Modernaintervenção2015

Trapézioperformance, intervenção, escultura2014

Turbulência nos Trópicosinstalação2014

Space Invadersrelevo intervernção2014

Sem Títulorelevo2014

Turbulênciavídeo instalação2014

Sem Títulovideo2014

Bermudasescultura2013

Ondas Curtasvídeo + foto2013

Bermudasescultura2012

Bermudasescultura2012

Água Forteesculturas2012

Vigilanteescultura2012

Esquecimento Ifotografia2012

Esquecimento IIfotografia2012

Três Graçasescultura2012

Obliviofotografia2011

Nebulosaescultura2011

Mercúrioescultura2011

Heliumescultura2011

Esquecimentofotografia2011

Bermudasmonotipia2011

Bermudasrelevo2010

Dragãozinhoescultura2010

Hermesescultura2009-2010

HERÓIescultura2009-2010

Ventaniaescultura2009-2010

Cadeiraescultura2009

Furiasfotografia2009-2010

Navefotografia2009-2010

Primeiro Diafotografia2009-2010

Um por todosescultura2009-2010

Uma diversão, um tormento, uma ocupaçãovideo2009-2010

Contatofotografia2009

Enveloperelevo2008

São Joãoescultura2008

Anubisescultura2008

Beira + Paisagemfotografia + performance2008

Paisagemfotografia2008

Contatomonotipia2008

Contato (Rio)intervenção2008

Mesaescultura2008

O Barqueirovideo2008

Laço + Colunavideo + fotografia2007

Hulkescultura2007

First Loveescultura | intervenção2006

Contato (Chicago)intervenção2006

Cesio 137intervenção2006

Catapultainstalação2005

Aquecedor + Envelopeescultura2005

Tempo de dizer Uminstalação2005

Horizonte de Eventosescultura2004

Relevos com coresculturas2004

Céu azul locoinstalação2003

Apegoescultura2003

Quem pode fica em pé, quem quiser que se deiteinstalação2003

Reator de dobraescultura2003

Sidônio e a Guitarraescultura2003

Verdãoescultura2003

Estalaçãoinstalação2002

Macacosintervenção2002

Qescultura2001

Novelo laranjaescultura2001

Paracildoperformance2001

Rabecaescultura2001

Sursum Cordainstalação2001

Um grande passo para mim,um pequeno passo para a humanidadeperformance1999

Baíaescultura2001

All rights reserved. Any work presented on this website or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the artist.

© wagner malta tavares